Book Ban Reports Offer Conflicting Views as Banned Books Week Begins

NEW YORK — Two reports released Monday paint a complex picture of the wave of book removals and challenges as the annual Banned Books Week begins for schools, stores and libraries nationwide.

The American Library Association (ALA) reported a significant drop in complaints about books stocked in public, school and academic libraries in 2024, as well as a decrease in the number of books receiving objections. However, PEN America documented a surge in books being removed from school shelves in 2023-24, with the number more than tripling to over 10,000 compared to the previous year. Notably, more than 8,000 were pulled from schools in Florida and Iowa, where laws restricting book content have been passed.

The two surveys, while seemingly contradictory, offer different perspectives on the issue.

The ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom recorded 414 challenges in the first eight months of 2024, encompassing 1,128 titles. This represents a decline from the 695 cases and 1,915 books challenged during the same period last year. The ALA acknowledges that many challenges may go unreported, as librarians often preemptively remove potentially controversial books or choose not to acquire them.

While 2024 figures still exceed pre-2020 levels, Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, cautioned that the numbers predate the start of the fall school year, when Iowa’s previously suspended laws will be reinstated. “Reports from Iowa are still coming in,” she said, “And we expect that to continue through the end of the year.”

The ALA defines a “challenge” as a formal, written complaint seeking the removal of materials due to content or appropriateness. They do not track the precise number of books actually withdrawn.

PEN America, on the other hand, gathers its ban data from local media reports, school district websites, school board minutes, and partners like the Florida Freedom to Read Project and Let Utah Read. They rely primarily on local media and reports from public librarians. The organizations’ differing definitions of “ban” contribute to the discrepancies in their numbers.

The ALA considers a ban to be the permanent removal of a book from a library’s collection. Temporary removal for review and subsequent return does not constitute a ban, but is registered as a single “challenge.” However, PEN defines any withdrawal, regardless of duration, as a ban.

“If access to a book is restricted, even for a short period of time, that is a restriction of free speech and free expression,” stated Kasey Meehan, director of PEN’s Freedom to Read program.

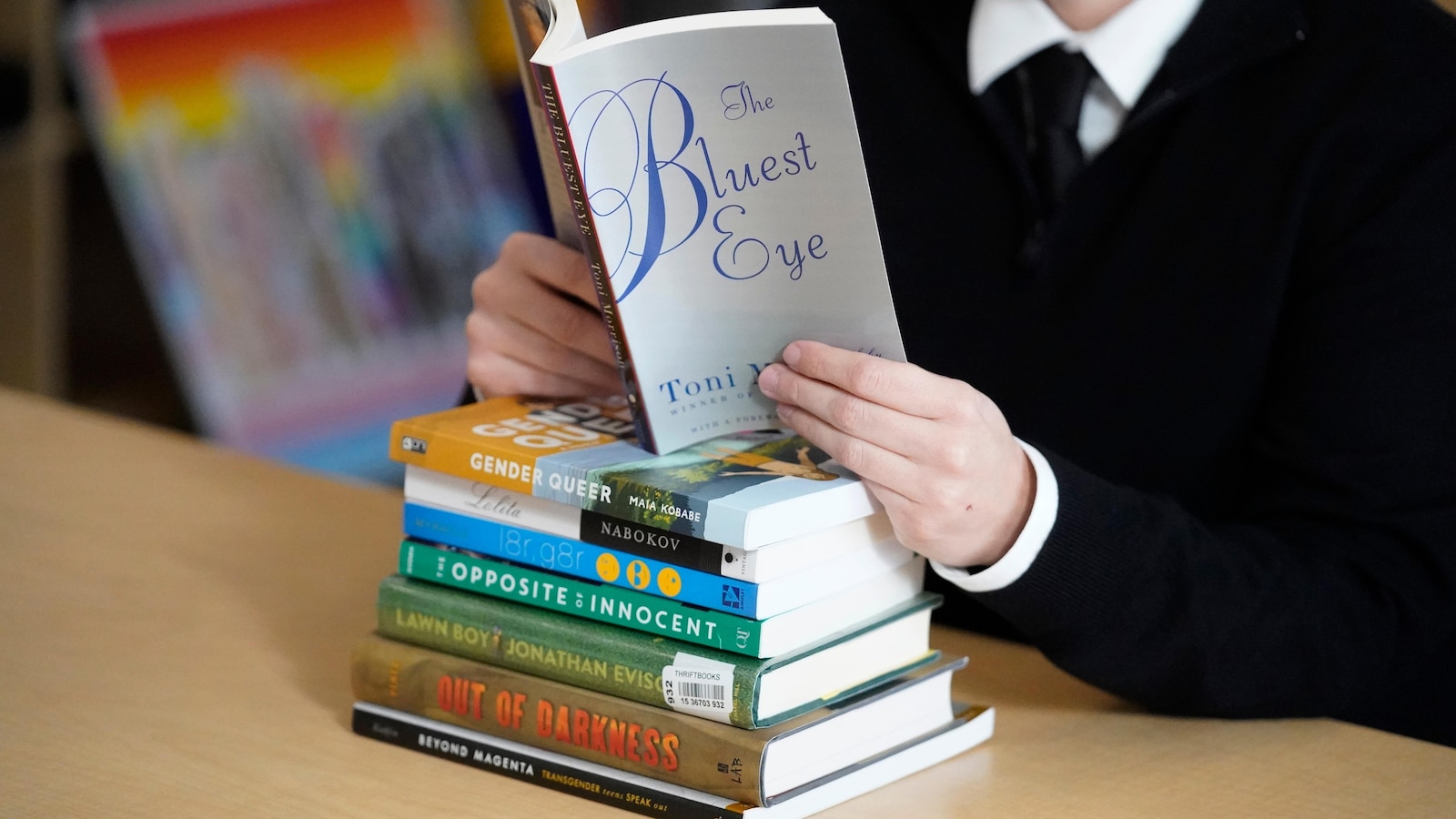

Both organizations note that a majority of the targeted books feature racial or LGBTQIA+ themes, including Meir Kobabe’s “Gender Queen,” Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” and “The Bluest Eye,” and Jonathan Evison’s “Lawn Boy.” While some complaints arise from liberals objecting to racist language in works like “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” the vast majority originate from conservatives and groups like Moms for Liberty.

Iowa’s law, passed last year by the Republican-controlled statehouse, prohibits school libraries from carrying books depicting sexual acts. It also mandates schools to make their library collections publicly accessible online and provide instructions for parents to request the removal of books or other materials. Many districts already had these systems in place.

Following legal challenges from LGBTQIA+ youth, teachers, and major publishers, a federal judge temporarily halted key provisions of the law in December. However, a federal appeals court lifted the hold last month, leaving room for further legal action.

Records requests filed by the Des Moines Register with Iowa’s 325 districts revealed that nearly 3,400 books were removed from school libraries in compliance with the law before its suspension. In Davenport, one of Iowa’s ten largest districts, books like Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale,” Kabobe’s “Gender Queer,” and Morrison’s “Bluest Eye” were among nine titles taken out of circulation.

After the law’s passage, district staff were instructed to review books available to students, according to Sarah Ott, Davenport’s district communications director. “If any books were preliminarily identified as potentially violating the new law, building staff referred the books to district administration for official review,” Ott explained. The district employs a pre-existing review process to ensure compliance with the law.

Banned Books Week, running through Sunday, was launched in 1982 and features readings and displays of banned works. It is supported by the ALA, PEN, the Authors Guild, the National Book Foundation, and numerous other organizations. Filmmaker Ava Duvernay serves as honorary chair, while student activist Julia Garnett, an opponent of book bans in Tennessee, holds the youth honorary chair position. Garnett was recognized as one of 15 “Girls Leading Change” by first lady Jill Biden during a White House ceremony last fall.

“We observe Banned Books Week, but we don’t celebrate,” Caldwell-Stone stated. “Banned books are the opposite of the freedoms promised by the First Amendment.”

___

Associated Press writer Hannah Fingerhut in Des Moines, Iowa, contributed to this report.