Giant: Roald Dahl’s Legacy on Trial at the Royal Court Theatre

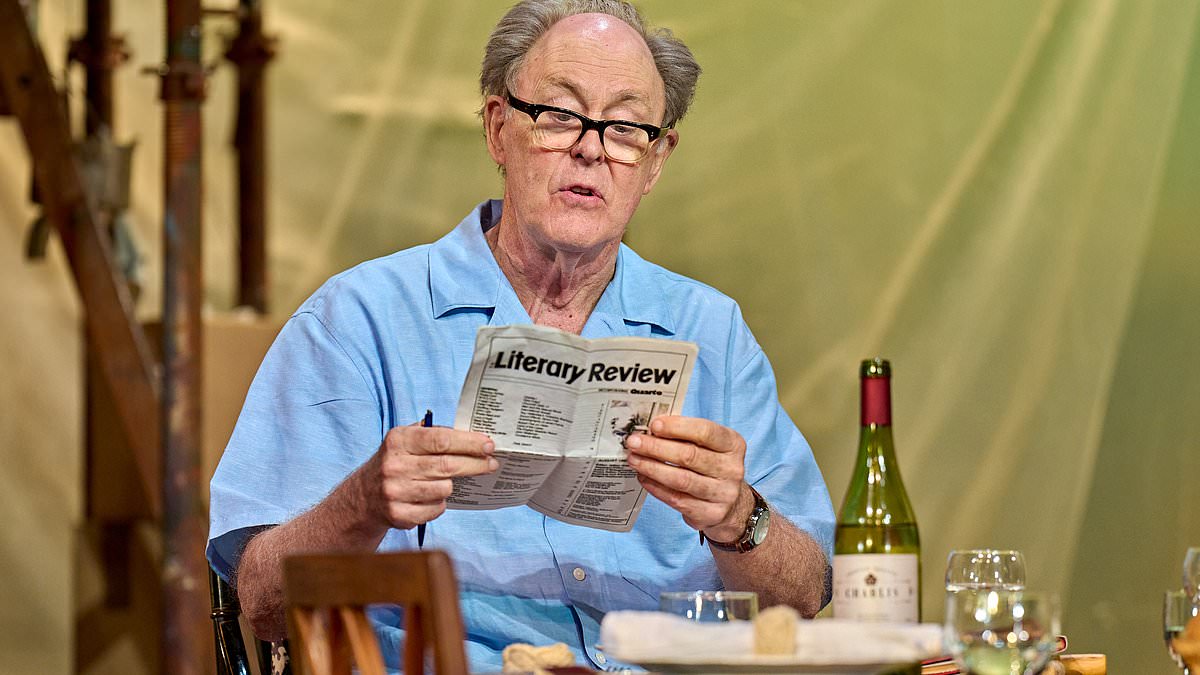

Best-selling children’s author and Second World War fighter pilot Roald Dahl is the latest historical figure to be put in the dock of public opinion and held to account for historical racial slurs. The court in question is the Royal Court Theatre in Chelsea, where Dahl is appearing in the shape of John Lithgow – best known as Winston Churchill in The Crown and from the TV series Third Rock From The Sun.

Mark Rosenblatt’s new play Giant examines the fallout from revolting anti-Semitic insinuations Dahl made in 1983 in a review of a book – God Cried – by Tony Clifton and Catherine Leroy, about the bombing of Lebanon the previous year. The setting is a rickety garden extension in Dahl’s country home in Buckinghamshire. He is going through proofs of his new book The Witches, attended by his British and American publishers, both of whom happen to be Jewish.

Trouble comes when his nervous, otherwise admiring American publisher (Romola Garai), seeks an apology for his poisonous remarks to appease the American market. Not only is Dahl unwilling, he lays into her too. But what is really shocking and impressive about Nicholas Hytner’s production is not that Dahl is exposed – this is a matter of public record. Instead, it’s the fact that the play is a violent, incendiary provocation. It says things that many people – Jews, Israelis, anti-Semites and the impartial multitude – may be thinking, but are too afraid to air in public. It’s not simply about Dahl, it’s about all of us. And, with all-out war looming in the Middle East, its timing couldn’t be grimmer.

At moments last night Lithgow’s brilliantly, brazenly unapologetic performance reduced the theatre to shocked, breathless silence. And he’s a Dahl ringer too. But Rosenblatt’s play also dares to show another side to him. His scathing wit that won him friends as much as enemies, how he glosses his truculent cruelty as his being ‘a direct sort‘, and excusing himself with his famous back pain.

All of this is a cue for Dahl to be roundly rebuked – and this Garai’s intimidated US publisher does with excoriating rage, identifying him as a nasty belligerent child for holding an entire people to blame for the actions of a single government. But, as the appeasing English publisher, Elliot Levey urges her to ignore Dahl as he did playground taunts, or his aunt’s hideous wallpaper. And Rachel Stirling as Dahl’s fiancé tries to keep the peace with icy Englishness, fearful Roald will spoil his chances of a knighthood.

The play goes off the boil after the interval, but it retains a powerful sense that all the characters are no better or worse than any of us. The message is that this ugly, persistent, question of anti-Semitism is something we all need to take care of, as a matter of extreme and present urgency.